How competition, not consumers, shapes plant chemistry

Plants are chemical powerhouses.

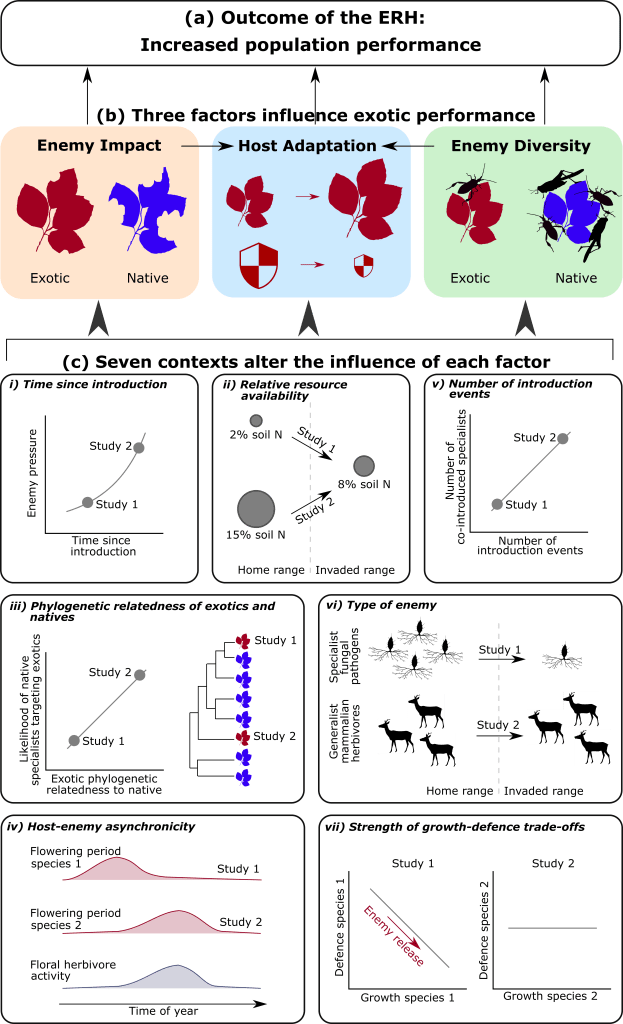

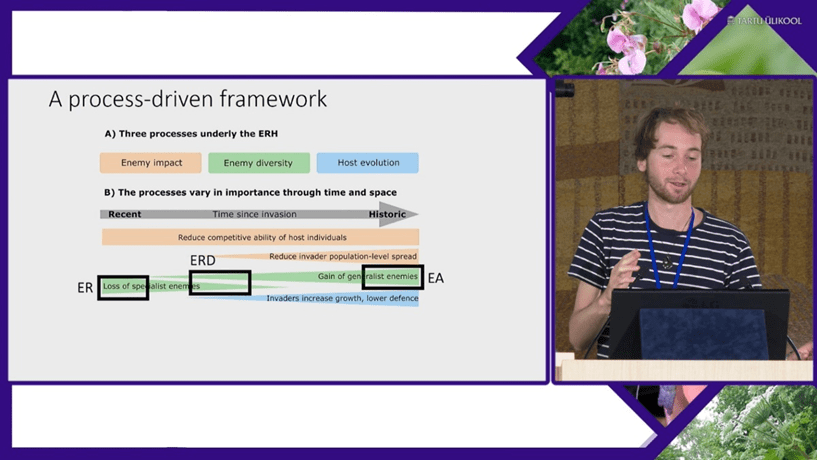

They make a huge range of chemicals. Some help them grow, others protect them from pests or stress. For years, scientists have thought these chemicals mainly evolve because of herbivores and diseases. But new research suggests something different: the plants growing next to you might matter more than who is eating you.

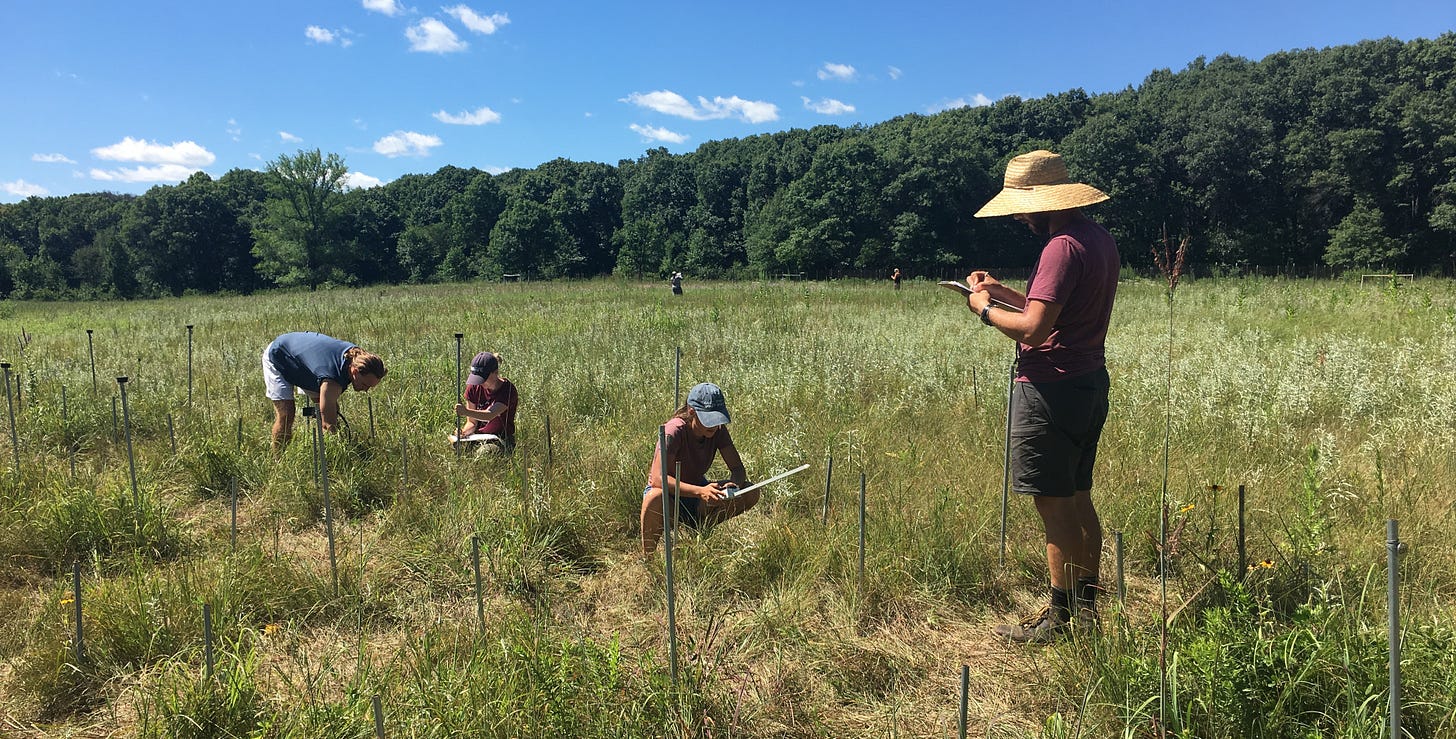

A study looked at two species in a long-term grassland experiment in Minnesota: Andropogon gerardi (also known as big bluestem, which is a tall grass) and Lespedeza capitata (roundhead bush clover; a nitrogen-fixing legume).

The team tested how these plants’ chemistry changed when they grew alone or in mixed communities, and when insect and fungi enemies were either present, or reduced with pesticides.

The findings were surprising. Both species grew better when pests were reduced, but their chemical make-up didn’t always change.

For A. gerardi, the chemistry stayed almost the same no matter the treatment. This suggests the grass relies on built-in defences rather than changing its chemistry when stressed.

L. capitata, on the other hand, reacted strongly to its neighbours. When surrounded by other species, it produced more amino acids and phenolic compounds – signs of stress – and less sugar. This means competition, not herbivory, was the bigger challenge.

Why does this matter?

First, it questions the old idea that herbivores are the main reason plants have such diverse chemistry. At least in the short term, who you grow next to can be more important. Second, it shows species respond differently. The grass seemed to thrive in mixed plots, while the legume struggled – both in growth and in chemical balance.

These differences could affect whole ecosystems, from nutrient cycling to how plants interact with insects.

The study also shows how complex plant responses are. Chemicals that dissolve in water and those that dissolve in fats behaved differently, and overall pest damage was low in the year studied. Even so, the evidence points to neighbours as key drivers of chemical change.

For ecologists and land managers, predicting how plants respond to climate change and biodiversity loss means looking beyond herbivores. As plant communities shift, their chemistry will shift too – and that could change how ecosystems work.

Future research should test more species and sample over time to catch short-term changes. For now, this study offers a simple lesson: in the chemical lives of plants, competition can matter more than consumption.

Read more:

Joshua I Brian, Adrien Le Guennec, Elizabeth T Borer, Eric W Seabloom, Michael A Chadwick, Jane A Catford, Plant neighbours, not consumers, drive intraspecific phytochemical changes of two grassland species in a field experiment, AoB PLANTS, Volume 17, Issue 6, December 2025, plaf071, https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plaf071

Article originally posted on KCL’s Spheres of Knowledge