Biological invasions are one of the five biggest threats to global biodiversity. On the face of it, this doesn’t make sense: how can exotic species with no previous history in a given location do so well and outcompete native species? The most popular hypothesis to explain this is the Enemy Release Hypothesis (ERH). This hypothesis states that exotic species leave their natural enemies behind when being introduced beyond their home range, releasing them from top-down regulation and enhancing performance in their invaded range. Despite this intuitive basis, evidence for the ERH is inconsistent. Further, while many studies demonstrate that exotic species lose enemies, they do not explicitly link this loss with increases in exotic performance. We therefore still do not understand whether enemy release can explain high exotic performance, and under what circumstances if so.

A semi-eaten plant in our MechER experiment…

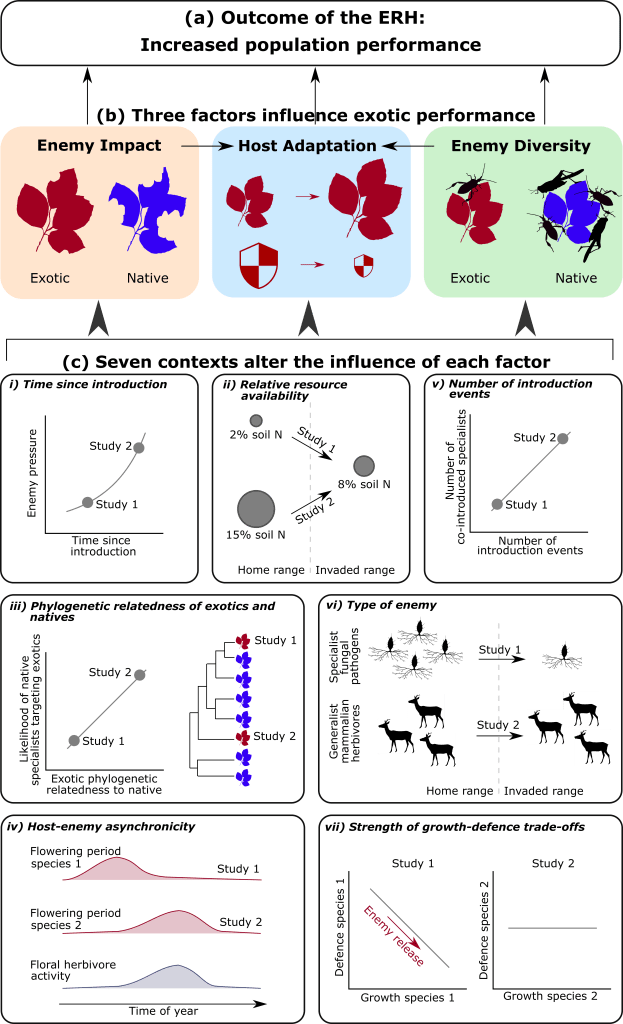

To address this, we have proposed a new framework for the ERH (Fig. 1), that has just been published in Ecology Letters. Our framework emphasises exotic performance as the key outcome of the ERH (Fig. 1a), with three factors – enemy impact, enemy diversity, and host adaptation – that influence performance (Fig. 1b). We then explore seven contexts that modulate the effect of these factors (Fig 1c): (i) time since introduction; (ii) resource availability; (iii) phylogenetic relatedness of exotic and native species; (iv) host–enemy asynchronicity; (v) number of introduction events; (vi) type of enemy; and (vii) the strength of growth–defence trade-offs.

We argue that our framework is more mechanistic and predictive, enabling better understanding of how and when enemy release can facilitate invasion. Our approach helps explain the ‘context-dependence’ in previous support for the ERH (something which is important to grapple with!). The framework also shows that many different enemy-related invasion hypotheses just represent different factor/context combinations, bringing theoretical clarity – we don’t need a new hypothesis for every new set of observations. We hope that our paper will encourage more explicit testing and reporting of the factors and contexts of the ERH in future studies on enemy release. This will enable effective synthesis, and more mechanistic insights into the role of enemy release in global invasions.

Full paper: Brian, J. I., & Catford, J. A. (2023). A mechanistic framework of enemy release. Ecology Letters.

Figure 1: A mechanistic reframing of the enemy release hypothesis. The enemy release hypothesis as an explanation for (a) increased exotic performance is the product of (b) three factors, which are modulated by (c) seven contexts. Three factors: 1) the difference in per-capita effect of enemies (compare damage on leaves); 2) the difference in enemy diversity, which incorporates enemy abundance (number of individuals) and richness (number of species); and 3) host adaptation, which involves changes in exotic growth (plant size) and defence (shield size). The influence of these factors and our ability to detect them changes with seven contexts. Each panel in (c) shows two hypothetical studies that examine different levels of a given context, and so would give contrasting support for the ERH.